Memory Ownership Models: When JavaScript Meets Native Code

You're building a React Native app that processes video frames. Each frame arrives as an ArrayBuffer in JavaScript from a camera feed, a network stream, or a file. You decide to delegate the heavy lifting to native.

You pass your ArrayBuffer to a native module, let it do the work, and get the results back. Simple, right? Well, it depends.

If you keep things synchronous, everything works. But the moment you try to optimize further by offloading work to a background thread, you discover that mixing JavaScript's garbage-collected world with native code's explicit memory management isn't as straightforward as it seems.

In this article, we will take a closer look at those two worlds and what happens under the hood.

The Synchronous Success Story

Let's start with the simple case: synchronous processing. You pass an ArrayBuffer to native code, it processes it immediately, and returns.

const pixels = new ArrayBuffer(1920 * 1080 * 4); // 4K RGBA image

nativeModule.applyFilter(pixels); // Synchronous call

// Done! Buffer is processedOn the native side, you get direct access to the buffer's memory:

// Native side

void applyFilter(jsi::Runtime& runtime, jsi::ArrayBuffer buffer) {

uint8_t* pixels = buffer.data(runtime); // Raw pointer

size_t size = buffer.size(runtime);

// Process the image using optimized native libraries

processImageFilter(pixels, size);

// Function returns, buffer is still valid

}Why is it faster? Native code can use mature processing libraries like OpenCV that operate directly on raw memory and automatically leverage SIMD or hardware acceleration. JavaScript simply doesn’t have equivalent low-level tools today, so native lets you tap into highly optimized routines that already exist.

Asynchronous Processing

But then you think: "What if processing takes longer? I don't want to block the JavaScript thread while native code does heavy work."

So you try to optimize by offloading the work to a background thread:

void processAsync(jsi::Runtime& runtime, jsi::ArrayBuffer buffer) {

uint8_t* data = buffer.data(runtime);

size_t length = buffer.size(runtime);

// Offload to background thread for better performance

backgroundQueue.async([data, length]() {

processImage(data, length);

});

}This seems reasonable. You capture the raw pointer and length, queue the work, and return immediately so JavaScript isn't blocked. But this is where things break down.

By the time processImage(data, length) actually executes on the background thread, the data pointer may be pointing to nothing, or worse, to memory that's been reused for something else entirely.

Memory Management

To understand what really happened here, we need to look at how each world manages memory:

JavaScript: Automatic with Garbage Collector

Most JavaScript developers live in a world where memory just works:

const buffer = new ArrayBuffer(1024);

// Use it

// Forget about it

// GC cleans it up eventuallyYou never think about when memory gets freed. You never worry about dangling pointers. And you definitely never coordinate access between threads. There's only one thread anyway.

Under the hood, the JavaScript engine (V8, JavaScriptCore, Hermes) allocates this buffer in its managed heap.

For an ArrayBuffer, the engine creates two parts: an object header and the backing store.

- The object header is typically ~16-24 bytes and contains metadata like the buffer's type, length, and a pointer to the actual data.

- The backing store is the actual memory where your 1024 bytes live, which often gets allocated separately for larger buffers.

The engine then tracks this object in its garbage collection system, adding it to the object graph so it knows what's still in use.

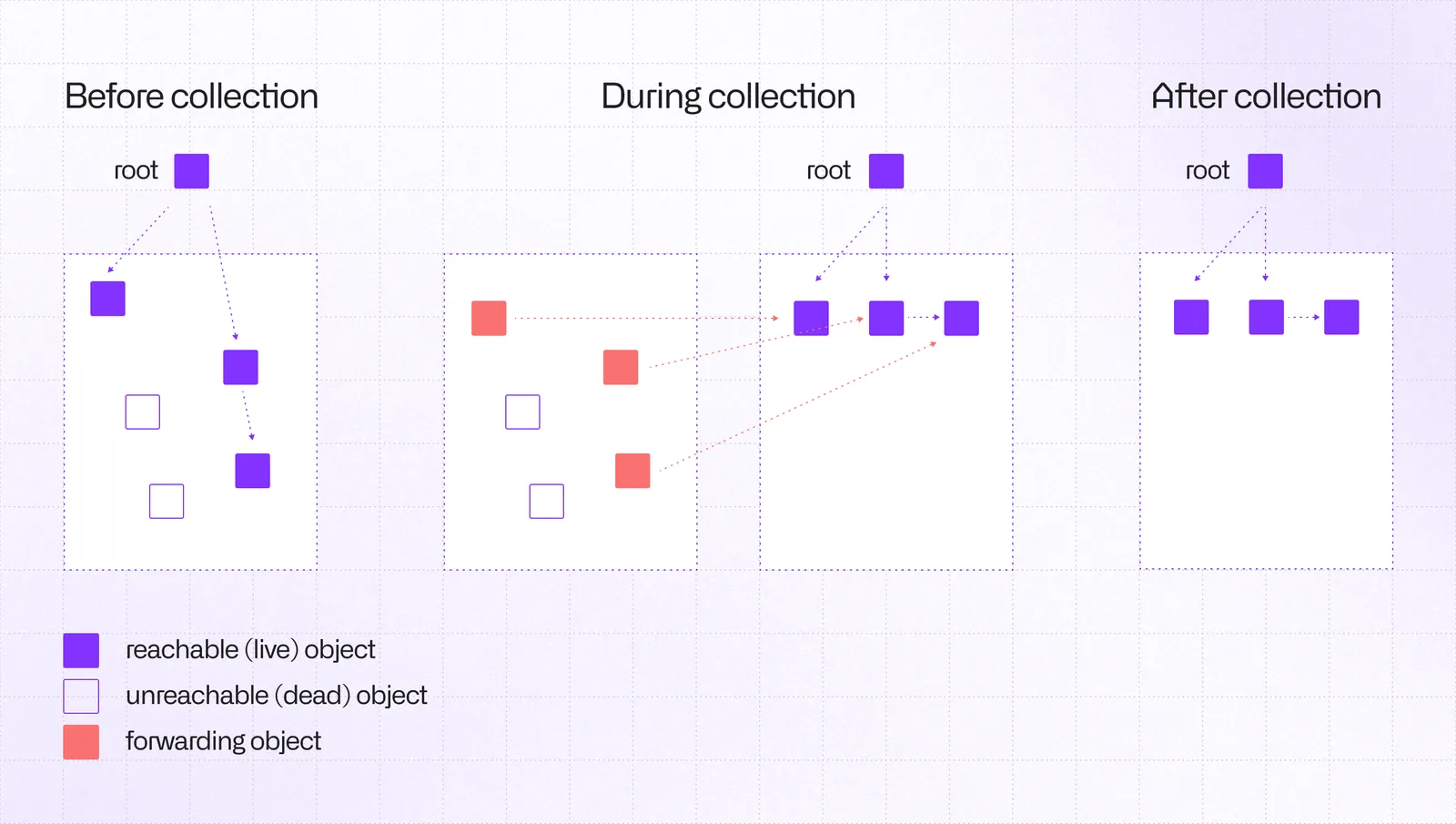

When your ArrayBuffer becomes unreachable (no references from any GC roots), the collector eventually kicks in. It marks reachable objects, sweeps away the unmarked ones, and optionally compacts memory to reduce fragmentation (moving objects closer together to eliminate gaps left by freed objects). You don't get to choose when this happens.

But this simplicity comes with trade-offs. GC runs when it wants, not when you want. Modern garbage collectors (including Hades used in Hermes) are mostly concurrent, running in the background without pausing JavaScript execution. You can't say "free this now" or "keep this alive". You're just along for the ride.

Native code: Explicit control

Native code operates under different rules:

void processData(uint8_t* data, size_t length) {

// Who allocated this?

// When will it be freed?

// Can I use it after this function returns?

// What if another thread modifies it?

}That pointer data is just a 64-bit integer (on 64-bit systems) containing a virtual memory address.

- It could point to the stack (local variables), the heap (dynamically allocated memory) or a memory-mapped region (memory mapped directly from a file or shared between processes).

- It might be read-only or writable.

- The code or thread that allocated it could free it at any moment, invalidating the pointer.

- And while you're reading this, another thread might be writing to

data[100]right now.

Every raw pointer, a direct memory address without any safety wrapper, is a contract. To use memory safely, you need to know who's responsible for freeing it, how long it's valid, whether it can change while you're using it, if multiple threads can access it, whether it's properly aligned, and what the valid address range is. The compiler won't check any of this for you.

Native code gives you control but demands discipline. The compiler won't save you from use-after-free bugs (accessing memory after it's been freed) which can cause undefined behaviour (e.g. corrupt data or crash your program). The runtime won't detect data races. And the CPU? It'll happily load whatever garbage is sitting at that address, or crash with a segmentation fault if the OS no longer has that memory address mapped to real memory.

JSI: smart wrappers around GC-managed objects

JSI sits between these two worlds.

A jsi::Object (and all of its subclasses, such as jsi::ArrayBuffer) is essentially a smart wrapper around a GC-managed value. It keeps the underlying JavaScript object alive and lets the engine update the internal pointer if the object moves during compaction. In practice, that means that as long as you stay inside the JSI API, things "just work" even when the garbage collector is doing its job.

Calling data(runtime) on jsi::ArrayBuffer gives you a raw native pointer into the backing store. That pointer is not a smart wrapper. If the engine decides to move the backing store, JSI will keep the jsi::ArrayBuffer object itself valid, but any raw pointer you previously captured will not be updated.

In Hermes today, ArrayBuffer backing stores are allocated in the C heap using malloc(), so they are not moved by GC compaction. However, this is an implementation detail, not a cross-engine guarantee, and JSI itself cannot promise that ArrayBuffer data is always non-movable. When you design APIs around raw pointers, you should think in terms of the abstract model (the data might move or be detached), not a single engine's current implementation.The Problems Begin

Let's go back to the previous asynchronous snippet, now that we know a bit about theory of memory management across JavaScript and native.

void processAsync(jsi::Runtime& runtime, jsi::ArrayBuffer buffer) {

uint8_t* data = buffer.data(runtime);

size_t length = buffer.size(runtime);

// Offload to background thread for better performance

backgroundQueue.async([data, length]() {

processImage(data, length);

});

}Here two things go wrong:

- The

jsi::ArrayBuffergoes out of scope whenprocessAsyncreturns, so the GC is free to collect it while the background work is still running. - You captured a raw pointer and length at the time you scheduled the work. If the backing store ever changed, that pointer would no longer describe the real buffer.

A more disciplined version keeps the jsi::ArrayBuffer alive and only asks for data and size inside the async work:

void processAsync(jsi::Runtime& runtime, jsi::ArrayBuffer buffer) {

auto sharedBuffer = std::make_shared<jsi::ArrayBuffer>(buffer);

backgroundQueue.async([sharedBuffer, &runtime]() {

uint8_t* data = sharedBuffer->data(runtime);

size_t length = sharedBuffer->size(runtime);

processImage(data, length);

});

}This pattern fixes two important problems:

- Lifetime: as long as the lambda is alive,

sharedBufferkeeps the JavaScript object alive, so the GC will not reclaim it. - Pointer freshness: you call

data(runtime)andsize(runtime)at the point of use, so you always get a pointer that reflects the engine's current backing store.

However, even with this pattern you are still responsible for everything outside JSI:

- The engine is still allowed (in principle) to detach or reallocate the backing store after you have obtained the pointer.

- JavaScript code can still mutate the buffer while native code reads it.

What Can You Do?

Given these challenges, what are your options?

Option 1: Stay Synchronous

Keep processing synchronous. This works perfectly, but blocks the JavaScript thread. For quick operations, this is fine. For longer operations, it hurts user experience.

In theory, any JS operation (including ones triggered from native) could cause GC compaction, so the safest pattern is to obtain the pointer as close as possible to where it is actually used.

Option 2: Copy the Data

Copy the buffer to native-owned memory before processing:

void processAsync(jsi::Runtime& runtime, jsi::ArrayBuffer buffer) {

size_t length = buffer.size(runtime);

uint8_t* copy = new uint8_t[length];

memcpy(copy, buffer.data(runtime), length);

backgroundQueue.async([copy, length]() {

processImage(copy, length);

delete[] copy;

});

}Copying gives you a simple and reliable boundary: once the data lives in native memory, your async work is entirely decoupled from GC behaviour or JS mutations.

The tradeoff is cost. Moving several megabytes per frame adds up quickly, and for high‑bandwidth workloads it can become the bottleneck.

Option 3: Native-owned buffers

Another approach is to allocate and manage the memory entirely on the native side and expose it to JavaScript as an ArrayBuffer. JavaScript can write into these buffers, but the memory itself stays under native control. That gives you stable, non-movable memory and safe async processing without lifetime surprises.

This is the model used by Nitro Modules, which exposes ArrayBuffers with clear ownership semantics. Nitro lets native code create owning buffers and treat JS-created buffers as non owning, preserving native lifetime guarantees.

func doSomething() -> ArrayBuffer {

let buffer = ArrayBuffer.allocate(1024 * 10)

print(buffer.isOwner) // <-- ✅ true

let data = buffer.data // <-- ✅ safe, we own it!

self.buffer = buffer // <-- ✅ safe

DispatchQueue.global().async {

let data = buffer.data // <-- ✅ also safe!

}

return buffer

}If you need zero-copy buffers in React Native today, Nitro's approach is the most complete solution available.

Unless JavaScript APIs can write directly into a native-provided ArrayBuffer, there will always be at least one copy. If the data starts in JS, you must copy it into native memory before doing any safe async work. Native-owned buffers avoid all further copies, but they can’t eliminate that first one unless the JS API itself supports writing into externally allocated memory.

Conclusion

Passing objects between JavaScript and native involves two very different memory models. JavaScript relies on a garbage‑collected heap with objects that may move or be detached, while native code works with raw pointers allocated and managed manually. JSI bridges these worlds by keeping JavaScript objects reachable and giving native code controlled access to their backing stores.

Synchronous use is mostly safe because everything happens within a single call, provided you obtain the pointer immediately before using it and avoid triggering additional JS execution during that window.

For asynchronous code, the picture is more nuanced. You can make async processing work by keeping the jsi::ArrayBufferalive and obtaining a fresh pointer at the moment of use, but you still need to account for GC behaviour and any JS execution that may occur before the work runs.

Alternatively, you can:

- copy into native‑owned memory to avoid these concerns entirely, at the cost of an upfront copy, or

- use native‑owned buffers (such as those available through Nitro) to get stable memory across async boundaries without repeated copies, as long as the data originates in native.

The one thing you should avoid is capturing a raw pointer and assuming it remains valid across time or threads.

Special thanks to Tzvetan Mikov (@tmikov) for the additional context, explanations, and careful review.

Learn more about Performance

Here's everything we published recently on this topic.